Contributors:

Jamie Marina Lau, Nayuka Gorrie, Jumaana Abdu, Justin Clemens, Martyn Reyes, Xen Nhà, Alison Whittaker, Cherine Fahd, Madison Pawle, Em Meller, Lucy Van, Snack Syndicate, Scott Limbrick, Zhi Cham, Samantha Floreani, Kat Gledhill-Tucker, Darcy Hytt.

From the editors’ note:

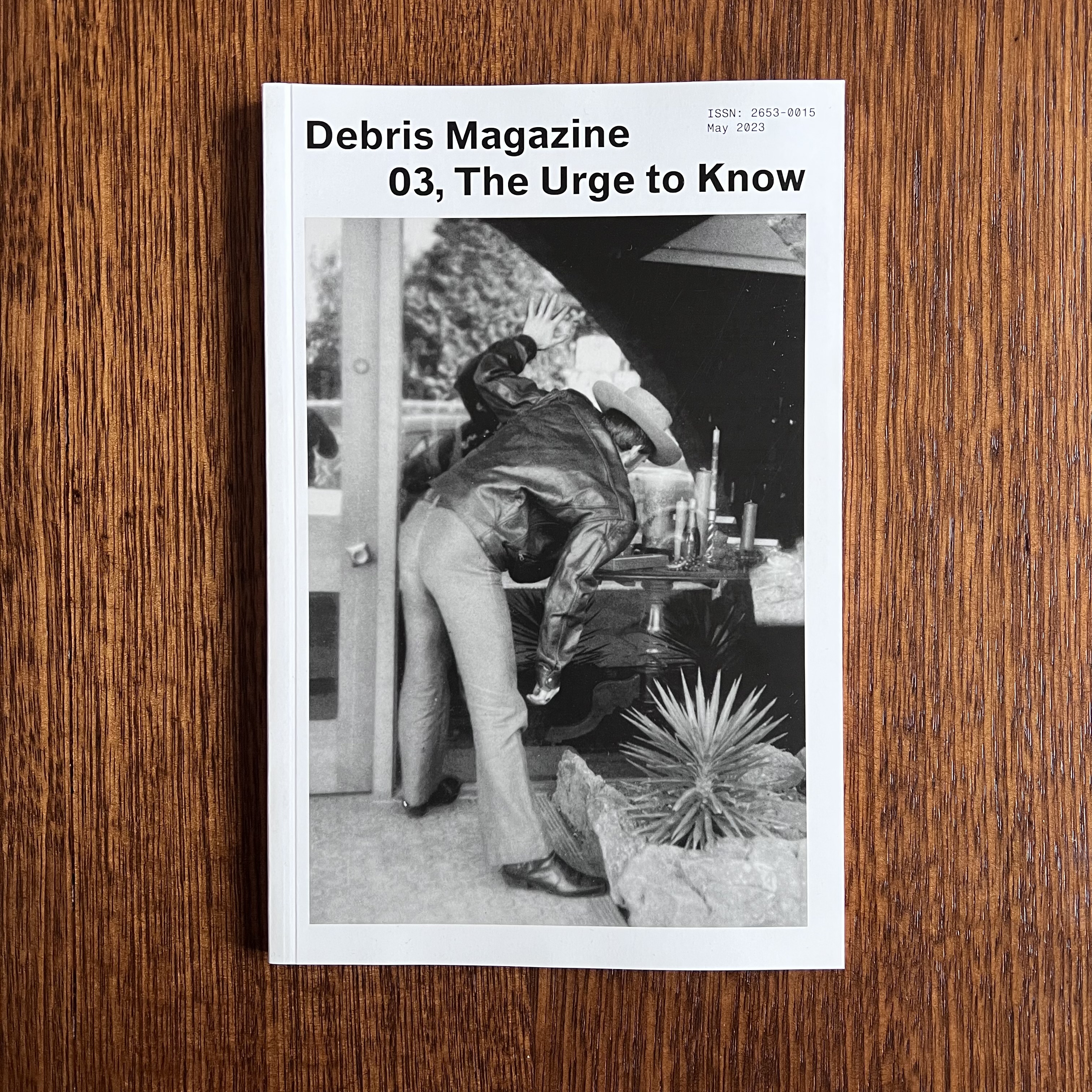

As a child encounters their own sentience, a fountain erupts.

We begin to find ourselves with an appetite for knowledge, which propels us into the world and whatever sense is to be made of it. As this grows with and through the body-a way to touch, grasp, beyond the range of our own senses-this proclivity gradually gains a (more) conscious quality. Later still, and inevitably, a barrier emerges, and we become self-regulating, tempering the urge in order to prioritise other needs and yearnings. The compulsion towards knowledge, then, manifests and recedes over time, in public and in private, assuming the form of invitation, attachment, affliction.

This propensity is also infectious: our friendship began with the urge to know. The edifying yet accursed urge to know about others, about ourselves, about the world around us. As one of us declared, "the urge to know is adjacent to the urge to witness!"Just a couple of know-nothing wanna-know-it-all wannabes;' the other agreed. It materialised into an inside joke. As Etel Adnan once wrote, "... knowing is an extraordinarily strong bond. It establishes a kind of magnetic field between beings or even things, and intensifies and illuminates everything."

Yet, jokes aside, knowledge is social in more than one sense. As new forms of organising and sharing information emerge, our relationship with knowing has undergone astonishingly quick change. Today, entangled with search engines and social media, our ability to reveal and perceive information with varying degrees of directness intersects with a certain ease. We can present, consume and re-present what we come to know-subjectivity and self-delusion notwithstanding. When we come to know more and more and more, how does the urge to know bind us to the world? How is the flavour of that knowledge dictated by the third parties that act as its mediators?

This impulse towards knowledge bleeds across lines of consent and legality to encompass misinformation and conspiracy theories, data breaches, bureaucratic obfuscations, the privatisation of knowledge work, and the many kinds of surveillance that people are subject to-be it from employers, peers, landlords, corporations and/or governments. It waters the will to power. But it's also deeply enmeshed with scripturience and the drive towards art-making; not only to know but to process and unpack, to know that we don't know, to know others through the limits of self-knowledge. There will always be aspects of existence that are unknown and unknowable, that cannot be adequately expressed or inscribed, or which do not make sense at all. Even if information continues to be laundered freely through open-source encyclopaedias, comment sections and whistle-blowers alike, we will never see the "full picture"-simply because there is none. You cannot arrest knowledge. Perhaps this is what draws us to the urge. We cannot know, and yet we must.

When Julia and Elena asked us to be guest editors for this magazine, we leapt at the opportunity. Finally! To be able to put this provocation in front of others, to pass them the itch and see how they would scratch it. How would they interpret it, and what had they considered that we had not? We needed to know. The responses we received were joyous, absurd, introspective and surprising. Ultimately, we landed on 16 interpretations that resist foreclosure and welcome possibility-maxing the fountain's faucet, so to speak. And now we are extending the urge to you. (...)

Jamie Marina Lau, Nayuka Gorrie, Jumaana Abdu, Justin Clemens, Martyn Reyes, Xen Nhà, Alison Whittaker, Cherine Fahd, Madison Pawle, Em Meller, Lucy Van, Snack Syndicate, Scott Limbrick, Zhi Cham, Samantha Floreani, Kat Gledhill-Tucker, Darcy Hytt.

From the editors’ note:

As a child encounters their own sentience, a fountain erupts.

We begin to find ourselves with an appetite for knowledge, which propels us into the world and whatever sense is to be made of it. As this grows with and through the body-a way to touch, grasp, beyond the range of our own senses-this proclivity gradually gains a (more) conscious quality. Later still, and inevitably, a barrier emerges, and we become self-regulating, tempering the urge in order to prioritise other needs and yearnings. The compulsion towards knowledge, then, manifests and recedes over time, in public and in private, assuming the form of invitation, attachment, affliction.

This propensity is also infectious: our friendship began with the urge to know. The edifying yet accursed urge to know about others, about ourselves, about the world around us. As one of us declared, "the urge to know is adjacent to the urge to witness!"Just a couple of know-nothing wanna-know-it-all wannabes;' the other agreed. It materialised into an inside joke. As Etel Adnan once wrote, "... knowing is an extraordinarily strong bond. It establishes a kind of magnetic field between beings or even things, and intensifies and illuminates everything."

Yet, jokes aside, knowledge is social in more than one sense. As new forms of organising and sharing information emerge, our relationship with knowing has undergone astonishingly quick change. Today, entangled with search engines and social media, our ability to reveal and perceive information with varying degrees of directness intersects with a certain ease. We can present, consume and re-present what we come to know-subjectivity and self-delusion notwithstanding. When we come to know more and more and more, how does the urge to know bind us to the world? How is the flavour of that knowledge dictated by the third parties that act as its mediators?

This impulse towards knowledge bleeds across lines of consent and legality to encompass misinformation and conspiracy theories, data breaches, bureaucratic obfuscations, the privatisation of knowledge work, and the many kinds of surveillance that people are subject to-be it from employers, peers, landlords, corporations and/or governments. It waters the will to power. But it's also deeply enmeshed with scripturience and the drive towards art-making; not only to know but to process and unpack, to know that we don't know, to know others through the limits of self-knowledge. There will always be aspects of existence that are unknown and unknowable, that cannot be adequately expressed or inscribed, or which do not make sense at all. Even if information continues to be laundered freely through open-source encyclopaedias, comment sections and whistle-blowers alike, we will never see the "full picture"-simply because there is none. You cannot arrest knowledge. Perhaps this is what draws us to the urge. We cannot know, and yet we must.

When Julia and Elena asked us to be guest editors for this magazine, we leapt at the opportunity. Finally! To be able to put this provocation in front of others, to pass them the itch and see how they would scratch it. How would they interpret it, and what had they considered that we had not? We needed to know. The responses we received were joyous, absurd, introspective and surprising. Ultimately, we landed on 16 interpretations that resist foreclosure and welcome possibility-maxing the fountain's faucet, so to speak. And now we are extending the urge to you. (...)

Edited by Cher Tan and Jon Tjhia.

Designed by Zenobia Ahmed.Product Details

ISSN: 2653-0015

Printed in Narrm (Melbourne) by Printgraphics

Supported

- City of Merri-bek

- Yarra City Council

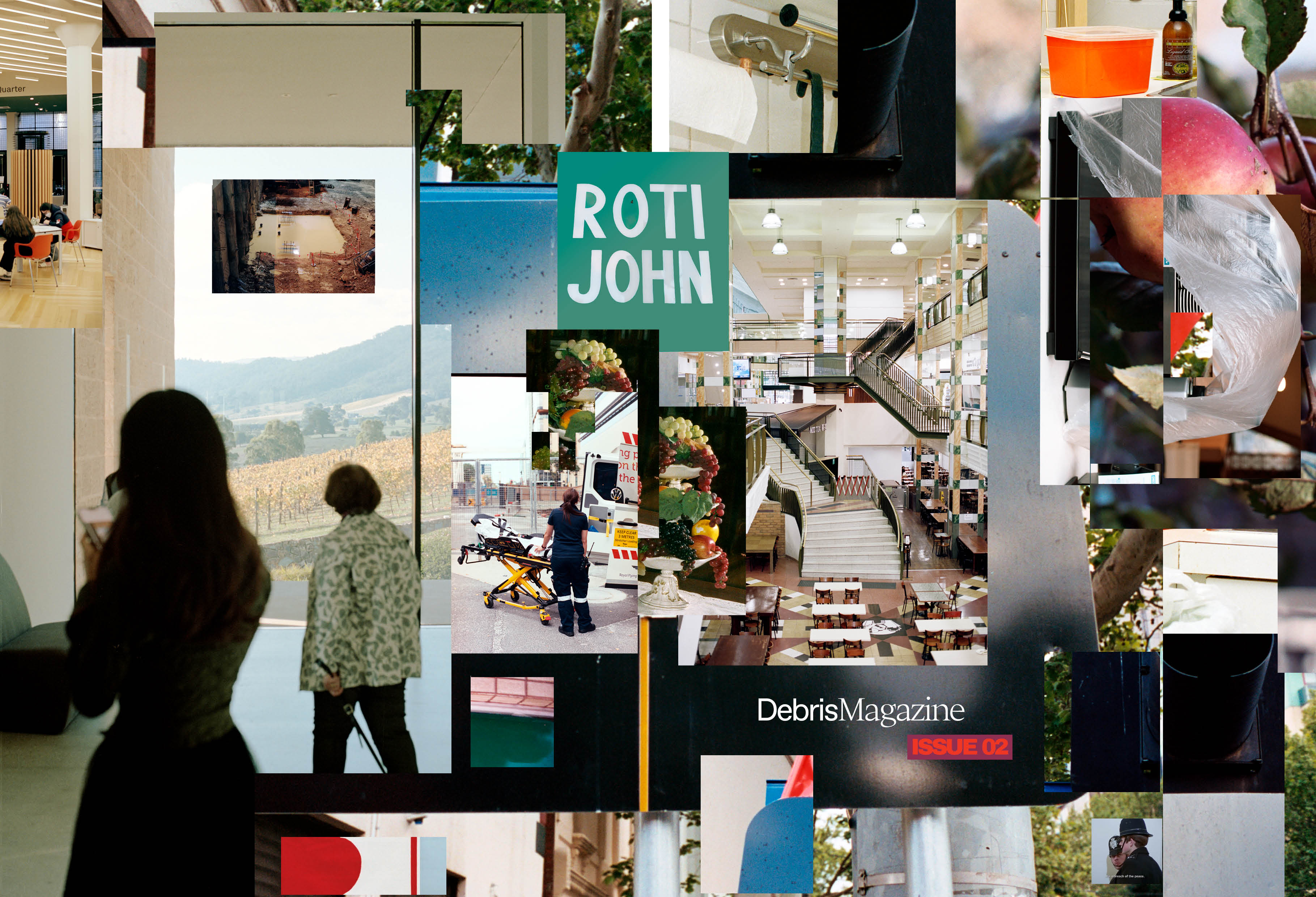

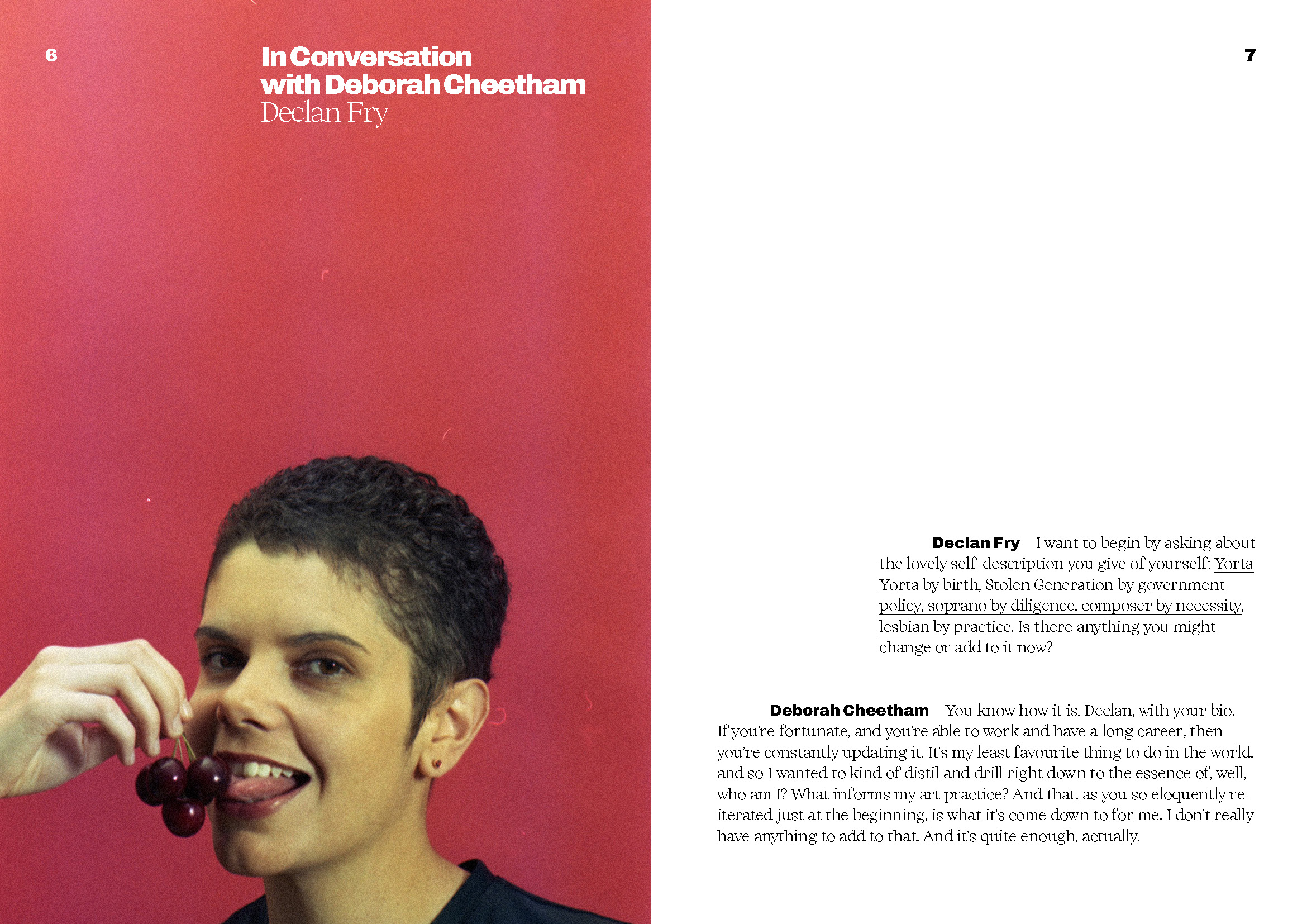

Our second issue features fifteen texts, a photo essay and illustrations that interrogate the theme of hospitality from all its angles. Contributors have embraced the ambivalent duality of hospitality in their offerings. They recognise the power of hosting and the subversiveness of the bad guest who refuses to sit in their allotted place. Despite this, hospitality is there in the small acts and the other spaces we shape for ourselves.

Guest edited by Alana Lentin, Anne Marie Te Whiu and Anna Yeon.

Guest edited by Alana Lentin, Anne Marie Te Whiu and Anna Yeon.

Product Details

ISSN: 2653-0015

132 pages on Envirocare

Released June 2022

Printed in Narrm (Melbourne) by E-Plot

Supported by

- City of Melbourne

- Darebin Council

- Moreland Council

Our inaugural issue features twelve texts, a photo essay and a comic strip exploring instances of imagined, delayed and anticipated grief. We unravel grief, looking within and peering beyond bereavement and loss. We look at grief that has been experienced personally, that is held collectively, that is carried in the body, and sedimented in place.

Co-edited by Anna Yeon, Maddee Clark, Emily Westmoreland, Danny Silva, Soberano and Elena Tjandra.

Co-edited by Anna Yeon, Maddee Clark, Emily Westmoreland, Danny Silva, Soberano and Elena Tjandra.

Product Details

ISSN: 2653-0015

Printed in Narrm (Melbourne) by Printgraphics

Supported

- Australian Council for the Arts

In this limited edition print-run, Debris Magazine welcomes you to the hidden world within "The Fine Print", a new short story by Ita-Marie Ralago. Set in modern-day Sydney, this tale follows Agnes, a single-mother immigrant who is contracted to work in a Professor's Northern Beaches home as his housekeeper. The contract itself, unusual in length and detail. The house begins to envelop her literary-absorbed son where they stumble upon the Professor's secret library, triggering a chain of mysterious happenings... Perhaps, don't forget to check the fine print.

About the author: Ita is a Fijian-Australian writer and hospitality worker living on Bundjalung land. She originally hails from Western Sydney, and as such, her writing is often a homage to the people and places she has left behind. Her work can be found in The Bengaluru Review and Griffith University’s Talent Implied.

About the author: Ita is a Fijian-Australian writer and hospitality worker living on Bundjalung land. She originally hails from Western Sydney, and as such, her writing is often a homage to the people and places she has left behind. Her work can be found in The Bengaluru Review and Griffith University’s Talent Implied.

Editor: Anna Yeon

Designer: Charlene Le

Printer: Press Print & MONSU Workshop

Paper: Colophon Harvest, Envirocare 100% recycled

Edition: 100